25

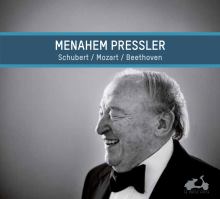

MENAHEM PRESSLER

Beethoven, meanwhile, increased the density of his discourse.

How was he

to break the barriers imposed on him by Classicism? What use was a new language

if the art of instrument making did not accompany him in his quest for innovative

sonorities? The

Pathétique

Sonata still bears the heading ‘for pianoforte or harpsichord’.

The keyboard remained a tool (though did he not say to musicians ‘What have I to do

with your wretched instruments when the spirit is upon me?’ when they complained

of the difficulty of his writing?) with which he depicted the theatre of the world and

dared, for the first time, no longer to address God. He admired Bach and regretted not

having worked with Mozart.

In the streets of Vienna, Schubert sometimes passed Beethoven but never

dared speak to him.

The composer of

Erlkönig

throws off the mask, because his

questions touch on the essence of music: what is the role of the artist in society when

he wishes, at the risk of his life, to take sole responsibility for his art without relying on

commissions? Like Beethoven, but more in sorrow than in anger, he plays on silences

and covert messages. What Vienna could tolerate, but did not wish to see, what

Metternich’s police prosecuted, but the Emperor supported, took shape under the pen

of Beethoven and Schubert.

These intersecting tales from Vienna, so close in

time and space, could only have been born on the

banks of a great river that diffused the new blood

of Europe. Vienna was ablaze with brilliance in

1800. Some have seen it as the dress rehearsal of

the century to come.