The mutual admiration between Wagner and Liszt went beyond their family

relationships.Wagnerwas in theprocessof reforming theoperahouse,whereas Liszt

was generally seen as a virtuoso, a beast of the concert hall. But Wagner acquired

very early on the conviction that his father-in-law – for Wagner’s second wife was

Liszt’s daughter Cosima –was also toiling to produce themusic of the future.

Liszt recreated on the piano excerpts from

Tannhäuser

or

Rienzi

in paraphrases whose

virtuosity encapsulates the full orchestra within the keyboard, and transcribed key

moments from

Parsifal

,

Der fliegende Holländer

and

Tristan und Isolde

with staggering

skill in sonicmimesis. The

Spinnerlied

from

Der fliegende Holländer

, the spinning chorus

that opens the secondact of theopera,whichLiszt transcribed in 1860 (incorporating

Senta’smotif), and

Isoldens Liebestod

(1867) no longer fall into the category of virtuoso

commentary, but seek to embody Wagner’s musical thought: here Liszt literally

appropriates his colleague’s language.

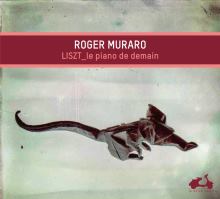

This quest for pure music in the context of an explicitly narrative, even descriptive

Romanticism, the principal focus of which remained the human passions, is the

central concern of the work with which Roger Muraro opens his Liszt recital, the

Fantasia and Fugue on B-A-C-H.

Liszt composed it in 1855 for the inauguration of the organ of Merseburg Cathedral,

built by Friedrich Ladegast. The work is a tribute to Bach, the letters of whose name

form the motif: B flat, A, C, B natural (which is ‘H’ in the German system of note-

names). Liszt adapted the original organ piece for his own instrument, the piano, or

rather, as the writing appears to confirm, conceived the work in parallel for the two

keyboard instruments, sacred and secular. He revised the score in 1870.

20 FRANZ LISZT