25

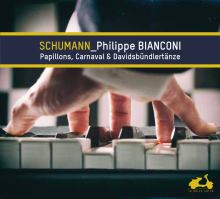

PHILIPPE BIANCONI

Yes, let’s get on to

Carnaval

. It’s a paradoxical work, at once extremely

‘enciphered’ yet at the same time one of the composer’s most accessible

pieces . . .

I like to imagine that Schumann had great fun writing this work, which is indeed

very cryptic, riddled with hidden meanings, but is nowadays one of his most

popular. Its variety of moods and atmospheres within a large-scale structure is

absolutely incredible, andwemove very quickly fromonemood to another –which

initially disconcerted the public.

Carnaval

, subtitled

Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes

(Little scenes on four notes), is

built on the lettersA-S-C-H: thatwas the name of the native village of Ernestine von

Fricken, a girl Schumann was in love with, and in German those letters correspond

to the notes A, E flat (Es), C and B (H). Schumann invents various combinations of

these notes which generate all but three of the pieces, in a very original conception

of variation form.

Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes

?When

Carnaval

begins, we don’t

know which notes they are. Not until the end of the eighth piece,

Réplique

, do we

discover the famous ‘Sphinxes’, very long notes at the bottom of the keyboard . . .

What’s your solution do you adopt for these Sphinxes?

I don’t play them. Of course that means the listener is excluded from the secret, but

in my view that’s part of Schumann’s little game – there’s something mysterious

that’s revealed to the performer but not to the audience. I know that a number of

great pianists have decided to play the Sphinxes. For my part, I’m convinced that

they shouldn’t be played; I don’t claim to be right, but in any case that’smy intimate

conviction.